The Buddha wasn’t a god; he was a man with eyes in his head. Any person with the ability to observe the world can deduce the simple facts the Buddha taught: suffering exists, things are impermanent, and the quality of our contentment isn’t necessarily related to our external circumstances. There are unhappy people in paradise and people who find contentment in hell. All things change, but there sits at the root of our nature certain enduring tendencies: the grain in the wood of personality, the slant of our inclination and the direction of our days.

The Buddha wasn’t a god; he was a man with eyes in his head. Nothing the Buddha taught needs to be taken on faith: you can test anything he said against your own experience, against what you yourself have seen and lived. If you don’t believe that suffering exists, scan the headlines in the nearest newspaper, tune into your favorite TV news channel, or ask the person next to you how things are going, really. Or try sitting with nothing but your own thoughts for ten, fifteen, or thirty minutes: as long as you can stand. How long does it take to sink beneath the skin of surface contentment to find the existential angst beneath?

If you don’t believe things are impermanent, try loving a child, an old person, or an elderly pet. Whenever you see someone change, grow, or age before your very eyes, you’re seeing impermanence in action. Or take a long view of your own relationships and your own self. How many of the people you loved ten, fifteen, or twenty years ago are exactly the same now as they were then? Take a good, honest look in the mirror. How have you yourself changed over the past decade? Even the most stubborn, entrenched personalities grow old, grow sick, and die.

The Buddha wasn’t a fortune teller; he simply was observant. He was, as I keep telling you, a man with eyes in his head. He closely observed the people around him, and he carefully monitored the coming and going of his own thoughts. The Buddha was like Isaac Newton sitting beneath an apple tree: he didn’t see anything particularly unusual, but he had the intelligence to notice the patterns that underlie the seemingly random nature of our days. Apples fall and seasons change. If you don’t believe me, go sit under an apple tree and see for yourself.

One morning this week, I wrote my journal pages outside, sitting at our backyard patio table. The bird feeder was empty, so there wasn’t the usual flapping, energetic throng of birds, but still there were squirrels foraging overhead, robins singing in the neighbors’ yard, and chipmunks scurrying through dead leaves. There wasn’t a single moment in even my quiet backyard that was truly quiet: there was a constant soundtrack of birdsong, animal rustlings, and insect humming.

You don’t have to set foot outside—you don’t have to move from wherever you’re reading these words—to experience the constant activity that is impermanence in action. Shut your eyes and turn your attention inward to where your thoughts chatter without ceasing. Try to follow the flow of your own thoughts: the way they inevitably jump from one thing to another. Even when the world around you is quiet and serene, your mind is agile and electric, jumping from one thought to another like a squirrel leaping from branch to branch. People erroneously think that meditation is about “stilling the thoughts,” as if this were possible. Stilling your thoughts is as possible as stilling your own heartbeat or the stopping the flow of blood in your veins. Even if you could do it, why would you want to?

Several weeks ago I spent two hours writing in downtown Boston at rush hour. I sat in a café facing a wall of windows with a clear view of a steady stream of people walking down the sidewalks on either side of a narrow one-way street. Occasionally, there was a burst of vehicular activity: at one point, several cars, a taxi , and a police SUV cruised down the street, followed by a lull in traffic. Although the cars moved in sporadic bursts, the flow of pedestrians was constant: people walking singly, in pairs, or loose groups; people talking on phones, gesturing to friends, or pointing to landmarks. One man stopped to take a picture on his phone, then three people passed in a kind of parade, each one steering a vendor’s pushcart: lemonade, hot dogs, Italian ice. Each person who passed was on an errand known only to them, and this activity never stopped during the two full hours I observed it. Trying to stop the rush hour flow of people walking, cars moving, and cyclists pedaling is impossible, as this activity is simply the nature of a city.

So is the nature of our minds. Our mind is a road at rush hour, with a constant traffic of thoughts moving past. Sometimes these thoughts come singly, one after the other, and sometimes they arrive in bursts of activity. Sometimes these thoughts slow and quiet, and we think we’ve reached the end of them…but inevitably they return, always arriving from unknown origins and wending toward unspoken destinations.

Sometimes our thoughts get stuck and we find ourselves endlessly obsessing over a single idea that returns again and again like a car that keeps circling the same block. But just as it’s impossible to count much less stop every single person that passes down a busy city street, it is impossible to stop the stream of our own thoughts. Thinking is the mind’s job, so it’s both foolish and futile to try to stop it. Why not try to cover your ears, stopper your nose, or paste your eyes shut?

The contentment that comes with meditation doesn’t come from stopping one’s thoughts; it comes from making peace with them. As I sat typing on my laptop and watching the stream of people pass by that rush hour coffee shop, I had no quarrel with any of them. If I had been sitting in traffic, I would have wanted it to move faster or slower: I would have had an interest in controlling it. But as a mere observer watching the people who pass, I didn’t have to worry about their pace, direction, or destination. When you simply observe your thoughts move through your mind like people passing down the street, there’s no need to worry over them. They’ll find their own way without any interference from you.

It isn’t our thoughts themselves but our impulse to control our thoughts that drives us crazy. Because the Buddha had eyes in his head, he realized this. If you spend time watching your thoughts, you’ll quickly realize that crazy thoughts, calm thoughts, happy thoughts, and angry thoughts all come and go. These thoughts arise and pass away without reason: there’s no need to try to excuse or explain them, just as there’s no need to excuse or explain the passing of people and vehicles during rush hour.

We suffer when we cling to impermanent things, and that includes thoughts. If we cling to the idea of “baby,” we’ll suffer when our child grows into an adolescent then adult. If we cling to the idea of “youth,” we’ll suffer when we see our bodies gray and wrinkle. If we cling to the idea “I am a good person,” we’ll suffer when angry, lustful, or selfish thoughts arise. If we cling to the idea “Meditation will make me peaceful,” we’ll suffer when we find our minds to be noisy with distractions.

The Buddha realized that all things, including our thoughts, are impermanent because he himself watched them pass. It was an observation anyone with eyes in their head could have made. Right now, look around at the people who pass, then look inside to the ebb and flow of your own thoughts. What can you hold? What can you take with you after you’re gone? If you have eyes in your head, you too will see the whole world is passing, and the only instant we can claim is the very moment at hand.

Aug 3, 2014 at 12:29 am

Remarkable…complex matters explained so very lucidly!

LikeLike

Aug 3, 2014 at 5:23 am

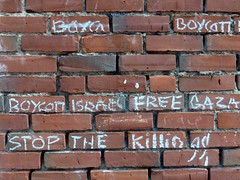

Lovely piece of writing and the street art’s a great accompaniment. Thanks!

LikeLike

Aug 3, 2014 at 7:49 am

This is a wonderful post. Words and images both.

LikeLike

Aug 3, 2014 at 1:16 pm

I love your posts about meditation. You explain this so well. I am still just getting the hang of meditation after years of doing it ….

LikeLike

Aug 4, 2014 at 6:18 pm

“the grain in the wood of personality”

brilliant!

enjoyed this post very much – all the bits and pieces of it

LikeLike

Aug 5, 2014 at 7:51 am

how many preachers can fit in a Buddha’s begging bowl ! ? :o)

LikeLike

Aug 6, 2014 at 3:43 am

I love the idea of stepping back and observing ones own thoughts. A wonderful post. Thank you. x

LikeLike

Aug 12, 2014 at 12:25 am

Love the street art–fundamentally impermanent. Great addition to the post!

LikeLike

Aug 15, 2014 at 9:34 pm

pretty deep and simple, good way to express your thoughts 🙂

LikeLike