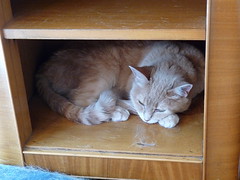

Yesterday morning, we put Bunny the cat to sleep. Earlier this month, after losing an alarming amount of weight, Bunny was diagnosed with kidney failure and spent a few days in the veterinary critical care unit, where our main goal was to get her healthy enough to come home. At home, we plied Bunny with food and an abundance of petting, committed to making her final days as comfortable and love-filled as possible.

This is, we’ve learned, how old cats often die. There’s the initial diagnosis, and veterinary care can extend their life long enough you can intentionally shower then with attention, making a conscious decision to (literally) love them to death. But inevitably, the disease wins: the disease always wins. You write the final chapter of a pet’s life knowing how the story ends but nevertheless fighting for every additional page, intent on cramming as much love and mercy as possible into a too-short narrative.

Bunny is the fifth cat we’ve lost since last March, the litany of grief counting out like rosary beads: Scooby, Louie, Snowflake, Groucho, Bunny. Grief doesn’t get any easier with repetition, but it does grow more familiar: an unwelcome but well-known guest who keeps returning. Although Scooby died suddenly, we euthanized the others after long, debilitating illnesses that afforded ample opportunity for anticipatory grieving. When you euthanize a pet after a long illness, you experience a dizzying array of contradictory emotions. On the one hand, you’re relieved your pet is no longer suffering; on the other, you’re stunned when an all-consuming struggle ends so suddenly, with no more need for the constant care and concern you’d lavished on this small, suffering creature.

Ever since Bunny came home from the critical care unit, she and I had settled upon a new routine. In the middle of the night, after I’d taken Melony the beagle out and in, I’d spend a half hour sitting cross-legged on the floor with Bunny nestled in my lap. At first, the goal of these vigils was to coax Bunny into eating: before getting down to the serious business of petting, I’d plop Bunny in front of a bowl of fresh food and watch her eat. Her final few nights, however, Bunny showed no interest in food or even water, so I’d gather her into my lap and clean her mucus-clogged eyes with a paper towel soaked in warm water. With one hand, I’d pet Bunny, who always loved to be cuddled, and with the other, I’d turn the pages of Anne Lamott’s Traveling Mercies, which seemed an appropriate choice of reading material while tending a dying animal.

I lost a lot of sleep these past few weeks sitting up with Bunny this way; last night, with no Bunny to fret over, I crawled right back into bed after taking Melony out. But I don’t regret the hours I spent petting Bunny in my lap while I read, wept, and prayed for just a little while longer. For the past few weeks, these midnight vigils spent cross-legged in my kitchen were my spiritual practice, the time I took to contemplate face-to-face the inevitable predicaments of old age, sickness, and death.

Bunny was 17 years old when she died, and she had been remarkably healthy during that time: as so often happens with old pets and old people alike, Bunny was healthy until she wasn’t. And until the very end, Bunny retained her essential sweetness, finding the energy to climb into my lap as soon as I’d settled on the floor, wanting nothing more than to be petted even when so many other physical discomforts threatened to overcome her.

During these late-night vigils, presumably influenced by Anne Lamott and her stories of spiritual seeking, I came to a heart-felt conclusion. God isn’t, I think, a bearded man on a throne but a being who sits cross-legged in the heavens, weeping and praying over the small, suffering world she holds tenderly in her lap.

Jan 18, 2016 at 7:53 pm

So sorry to hear about Bunny. I love the conclusion you drew from this experience. It is a beautiful picture!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Jan 18, 2016 at 8:47 pm

I am so sorry. I’ve been down that road so many times. I once lost 3 cats in 10 days, the same year i lost 6 overall. They were all about the same age and got old all at once..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jan 19, 2016 at 11:05 am

I’m so sorry for your loss. Take good care of yourself!

LikeLike

Jan 19, 2016 at 3:44 pm

Oh, my dear, I am so sorry for your loss. For your losses. May the memories of your animals be a blessing to you.

LikeLike

Jan 19, 2016 at 6:59 pm

Condolences. And hugs.

LikeLike

Jan 20, 2016 at 10:39 am

I just discovered your blog. So sorry about Bunny. I have been there through many. I pray for peace for your family.

LikeLike

Jan 21, 2016 at 8:29 am

My heart goes out to you.

LikeLike

Jan 21, 2016 at 3:02 pm

I’m so sorry, again. What you’ve written here is true and beautiful and difficult. They were all fortunate beings, as you are for knowing and loving them.

LikeLike

Jan 22, 2016 at 12:07 pm

I’m so sorry for your loss, Lorianne. My heart aches for you…

LikeLike

Jan 22, 2016 at 8:26 pm

lol

LikeLike

Feb 12, 2016 at 8:05 pm

I ran across this post again in my aggregator. When I first read it, we still had a cat. This time, our sweet old thing is gone. And I was amazed by the first photograph in this post — the look in your cat’s eyes — and how I recognized it from the last day of our cat’s life.

LikeLike

Feb 27, 2016 at 12:53 pm

What a beautiful post and tribute to a beloved pet. Ive traveled the animal hospice road many times. It’s never easy. Bunnie was a fortunate cat to have you.

LikeLike