March 2023

Monthly Archive

Mar 30, 2023

The earth never tires. This line from Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself always comes to mind on days like today when I come home from teaching bone-tired. At least there is something stronger than me, the earth continuing to turn day after day, year after year, pumping out perennials with abandon despite the discouragements of snow and cold.

The earth never tires because the earth doesn’t care. She doesn’t get her hopes up: the earth, in fact, neither hopes nor despairs. The earth continues to bear the weight of all our human souls, all our human heartbreak, while floating in the icy isolation of space. The earth neither waits nor wants–the earth simply turns, simply orbits, simply soaks sun on one side while blushing into shadow on the other.

The earth sometimes shudders with quakes but is largely immune from the paroxysms of human pain. The earth doesn’t care about your day, your week, your life: the earth simply soldiers on, heeding nothing but gravity and her own magnetic impulses. The sun is her star and the moon her vassal.

The earth never tires, but I do. I tire and I waver. I am prone to mountainous highs and valley lows. I ebb and flow–I tire by night and am revived by morning. I am heliotropic, my moods manipulated by light, hunger, and the vicissitudes of time. The earth never tires, but I do: I rise and fall with the sun, my spirit willing but my body weak.

Mar 28, 2023

I recently read Ruth Ozeki’s The Face: A Time Code, a slender volume written in response to an unlikely prompt: spend three hours contemplating your face in a mirror and explore what arises.

The thoughts that arise when a woman of a certain age considers her face are surprisingly deep. Initially, Ozeki’s observations are as superficial as you’d expect. Ozeki discovers she likes one eye more than the other, for example, and she notes the resemblances between her face and the faces of her white father and Japanese mother.

But if you spend three hours looking at a thing, you’ll eventually be forced to look more deeply. Ozeki notes the way faces are linked to identity: they are the public image we present to the world. Faces are like names: they are how we self-identify and how people judge us, for better or worse. Ozeki was born Ruth Lounsbury but took a pseudonym after her father asked her not to write about his family. A pseudonym is a mask–a crafted face–that both obscures and reveals.

As a middle-aged woman, considering how your face has changed over time is a psychological minefield. Ozeki describes her decision not to get a facelift and wonders if she should return to dying her hair. These seemingly insignificant personal decisions are rife with deeper issues. Ozeki explores, for example, the feminist implications of authorial headshots. Do glamor shots by professional photographers create an image that is impossible for an ordinary and aging author to live up to, or is the beautifying of one’s (female) face an inevitable part of marketing a book?

Ozeki is a Zen Buddhist, so her contemplation is also a meditation. The Buddha said impermanence surrounds us, and there is no better way to (literally) face that fact than to consider how your face has changed over time. Forget about seeing your face before you were born: can you accurately see the face in the mirror right now?

I’ve never spent three hours staring at my face, but years ago at a Dharma teacher retreat, we did an exercise where we spent several silent minutes looking into a random partner’s eyes. That activity was surprisingly eye-opening (no pun intended). Looking into an acquaintance’s eyes made me unusually self-conscious about my appearance and others’ opinions. Does this person think I look silly or stupid or ugly or boring? Should I smile or frown or maintain a neutral meditative expression? Should I try to tame my resting bitch face or just allow my face to rest in whatever expression it prefers?

The Face was published in 2015, years before the widespread masking of the COVID-19 pandemic, so the masks Ozeki describes in her book are the highly stylized masks of Noh drama. Ozeki describes the process of crafting a mask, and she describes how Noh performers embody their characters through voice and gesture instead of facial expressions.

In an unofficial sequel to The Face, last year Ozeki published an article exploring the impact of COVID masking and Zoom meetings on self-image. I remember the first time I walked outside after outdoor mask mandates had been lifted: I found myself smiling uncontrollably whenever I saw another bare face, and the experience of walking among many barefaced people was almost intoxicating.

One of the weird experiences of teaching remotely is having your face constantly on view–and visible to yourself–while most if not all of your students have their cameras turned off. It’s just you and your trying-so-hard-to-look-enthusiastic face trying to engage with the camera as you see nothing but your own thumbnail video surrounded by a sea of black squares. It’s like teaching into the void.

Facing one’s face and the issues of identity, aging, and superficial judgment is not for the faint of heart. What seems like a silly premise for a book is surprisingly profound.

Mar 22, 2023

The shrubs that line our driveway are sprouting their first tender leaves, and I can’t resist photographing them, just as I do every year. J and I joke that there is nothing more cliched than taking macro shots of flowers, but that doesn’t stop me from photographing crocuses or the first green shoots to emerge from our winter-blighted yard.

Yesterday Beth Adams posted a Facebook link to the Substack repost of her Cassandra Pages 20th anniversary post: yes, this is the convoluted way we read blogs nowadays, through mirror posts linked on social media. Regardless of how I found it, Beth’s post was filled with the slow, long-form writing she’s been doing all along, with photos of her botanical illustrations: a visual and intellectual delight.

In her post, Beth acknowledged how difficult it is to keep blogging for years without repeating yourself. This is a concern I abandoned long ago. I know I repeat myself year after year, just as the trees sprout the same old leaves in spring.

Mar 21, 2023

This past weekend, J and I walked at Broadmoor Wildlife Sanctuary, where we heard a single spring peeper singing. It was a lonely sound, but if one peeper is singing by day, there must be many more singing after dark.

Whenever I hear even one spring peeper, I think of May Sarton’s Plant Dreaming Deep. When Sarton first moved to New Hampshire, someone told her the winters are interminable there, but just when she’d give up all hope of Spring ever coming, she’d hear spring peepers. Hearing the peepers is a sign Spring would eventually arrive.

Yesterday was the first day of astronomical spring, and although there is no snow on the ground, the mornings are still cold. I haven’t worn sandals yet this year, but I will, eventually. I might doubt the arrival of that day, but the spring peepers know.

Mar 20, 2023

Today my Spring Break ends, as all things eventually do. I didn’t do as much grading as I would have liked–I never do–but I feel well-rested and…serene? Content? Ready to return to teaching? I suppose this is all any Spring Break can hope to accomplish: a pause to rest and reset.

I did a little of everything I enjoy this Spring Break: I read and walked and spent time with J and the pets. I went to Tower Hill with a friend and to the Museum of Fine Arts on my own. I went to the Zen Center and realized (again) how helpful and productive I will be when I (eventually) retire and have more time to go to practice and teach meditation: all the good stuff that gets squeezed to the margins or entirely blotted out when I’m busy Making a Living.

This has been the puzzle–my own personal kong’an–my entire adult life: how do you find the time and energy for Living while you are Making a Living? I haven’t solved that puzzle, but I’m learning to live with it. I’m learning how to sit with the question, as we Zennies like to say.

During my early adulthood, my perpetual puzzle was reconciling Zen and Christianity–was I Christian, Buddhist, or what? After approximately a decade of resting and wrestling with that conundrum–the task of my twenties–I finally gave up trying to answer the question. Am I Christian or Buddhist or both? Somehow, I just am who I am, and the need to sort, categorize, or label fell away along the way.

The task of my thirties was my divorce: who am I and how will I survive in the world if I’m not the perfect wife of my youthful idealism? This, too, is a question that didn’t get solved as much as dissolved: after a while, you stop wondering why you didn’t fit into the box of your own expectations. Eventually, you throw out the box.

The task of my forties was re-marriage and re-entry. Just because one coat didn’t fit doesn’t mean you give up wearing coats. Marrying J meant moving back to Massachusetts, where I’d gone to graduate school before moving to New Hampshire. My grad school and first-marriage days were sustained by the hope of becoming tenured faculty somewhere, someday. In my twenties and thirties, I had hopes for the moon, and in my forties I realized I’d fallen into a different kind of career that still managed to pay the bills.

Halfway through my fifties, I’m reconciling Living and Making a Living: what Buddhists call Right Livelihood. This particular balancing act will be, I suspect, the task of a lifetime.

Mar 18, 2023

On Wednesday, I went to the Museum of Fine Arts for this year’s (belated) birthday trip, just as I did last year. While I was there, I read the journal entry I’d written but never blogged last year:

It’s St. Patrick’s Day, and I’m having lunch at the MFA: my belated birthday trip. I’ve spent the past almost-hour wandering the galleries, not looking at anything in particular: just looking.

Several years ago, before the pandemic, A (not her real initial) and I coined the term “museum bathing” for this activity of wandering a museum, soaking up the space. They say spending time in the woods–what the Japanese call “forest bathing”–has a beneficial effect on one’s mental and physical health–and I’d argue the same is true of museums and other sacred spaces. The act of being in a space devoted to beauty has a healthful effect. I can feel the outside world and its worries falling away.

You could even go so far as to say a museum is like a forest–an indoor, curated one, with paintings and sculptures and tapestries instead of trees and rocks and streams. A museum is a kind of ecosystem: the individual galleries are microhabitats, and they all work together in a harmonious whole.

The challenge when you visit a large museum is seeing the forest for the trees. Usually when I visit the MFA, I have a specific exhibit I want to see, so I zip through galleries to get to that particular thing. Today, though, there isn’t anything in particular I’m here to see, so I am free to wander without destination, turning this way or that depending on what looks interesting at the moment.

I can wander from Greek statues to Egyptian mummies to Buddhas being restored to contemporary posters to postcards to Regency interiors and back. When you don’t have a destination, there is no hurry; instead of making good time, you can take your time, stopping to look when something looks good.

One of the delights of the MFA, like any good forest, is the abundance of places to sit–benches in front of individual art works, and tables, chairs, and occasional couches in visually interesting corners–and in a museum like a forest, every corner is interesting if you take the time to look.

So that is today’s task: to wander and watch, letting my inner eye guide me. There is no need to see everything, just a chance to find a secret, interesting vantage point to watch and wait.

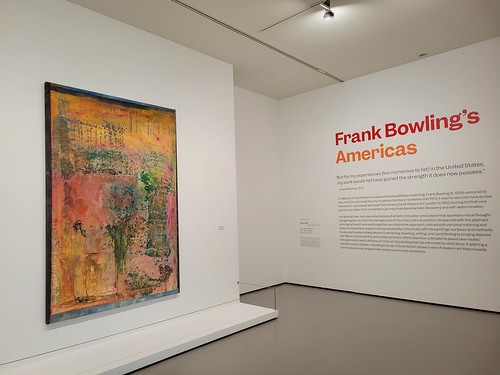

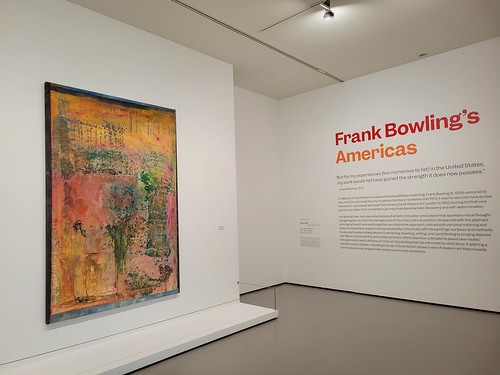

Although I wrote the text of today’s post last year, today’s photos are from Frank Bowling’s Americas, which is currently on view at the MFA.

Mar 17, 2023

It’s been more than three years since I’ve sung the Evening Bell Chant at the Cambridge Zen Center: yet another practice interrupted by the pandemic. But when three attendees at last night’s meditation intro class asked to hear the temple bell, I decided to show them the bell the best way I could, and that was by hitting it.

The Evening Bell Chant is a short–two- or three-minute–solo chant sung at the beginning of evening practice by someone who accompanies themselves on the big brass bell that sits like a tank in one corner of the Dharma room. It is my favorite chant, either to sing or listen to, largely because of the bell itself, which reverberates with a thrumming pulse. That sound spreads throughout the room–there is no missing or mistaking the bell when it is struck–and when you are the one hitting the bell with a worn wooden mallet, those vibrations thrum through your entire body. You hit the bell, but it feels like your own body is ringing.

The lyrics to the Evening Bell Chant are in Korean, with a translation in the back of the chanting book. The sound of the bell, those lyrics explain, cuts off thinking, and the sound of the bell coupled with the mantra repeated three times at the end Destroy Hell.

Hearing the sound of the bell,

all thinking is cut off,

Wisdom grows;

enlightenment appears;

hell is left behind.

The three worlds are transcended.

Vowing to become Buddha

and save all people.

The mantra of shattering hell:

om ga-ra ji-ya sa-ba-ha

om ga-ra ji-ya sa-ba-ha

om ga-ra ji-ya sa-ba-ha

Usually when I sing the Evening Bell Chant, I have to keep one eye on a laminated printout with the lyrics and pattern of hits in LARGE PRINT: there’s nothing worse than forgetting your lines or literally missing a (bell) beat when an entire Dharma room is listening. But last night, as soon as I sat on the cushion and picked up the mallet, the words came back like muscle memory. It was as if the bell itself were singing the words.

Mar 14, 2023

How can I describe today’s weather, with a nor’easter bringing overnight rain that is currently changing to snow?

First, I’ll note that most of our storms this year have brought more rain than snow, causing some locals to coin the term “pour’easter” to describe a winter storm that is more wet than snowy. Today’s storm was forecast as a traditional nor’easter bringing high winds and more than a foot of snow to Western parts of the state, but here in eastern Massachusetts, we’re experiencing a storm that is half pour and half nor: a pour-nor’easter?

Second, it’s just before 2:00 pm, and I’m wearing my third pair of pants, socks, and gloves of the day, having changed out of wet clothes after walking the dog in the morning and with J midday. I’ll probably have to change clothes again after getting home from an afternoon errand, it being a cold and drenching kind of day.

Third, while cleaning wet, sludgy snow from my car in advance of that aforementioned afternoon errand, I quietly coined a new term to describe pour-nor’easter precipitation: splat snow, based on the sound it makes when you brush it off your car and it lands as a clumpy puddle on the pavement below.

Mar 12, 2023

Yesterday, A (not her real initial) and I met at the New England Botanical Garden at Tower Hill for their annual orchid show, followed by lunch at our go-to place for ice cream and fried seafood.

I arrived at Tower Hill about fifteen minutes early and found a quiet corner outside the Orangerie to read. At any given moment on any given day, all I want is the time and spaciousness to read uninterrupted: a simple pleasure to sustain a busy life.

After we looked at orchids and art and before we talked over fried scallops, French fries, and onion rings, A and I walked the woods at Tower Hill, the trails a patchwork of snow, hardpack, and mud. Whereas the indoor conservatory was thronged with people admiring a panorama of orchids, A and I had the woodsy trails nearly to ourselves, trees in winter being drab and ordinary next to the splendor and allure of hothouse flowers.

A and I braved the modest climb (listed as “difficult” on the indoor trail map) up stone steps to the top of Tower Hill, where we saw Wachusett Reservoir framed in a palette of winter grays. We talked of being Women of a Certain Age, where you can still climb rocky paths but let younger hikers go ahead as you carefully pick your way up and (especially) down woodsy inclines, mindful of things you didn’t consider when you were younger, like asthma and osteoporosis and the potentially dire outcomes of a twisted ankle.

Over lunch, A and I talked of reaching a point where we have virtually no more fucks left to give, the ambitions of youth giving way to more practical concerns. Orchids are pretty in their prime, but forest trees last ages, growing gnarly, gray, and increasingly rooted and immovable. I’ve reached the time in my life where I am more like a tree than an orchid.

CLICK HERE for more photos from yesterday’s trip to Tower Hill. Enjoy!

Mar 8, 2023

We have just enough snow this year to frame the snowdrops. Our yard has two clusters of snowdrops: one under the eaves, and one in the tiny patch of grass between our Japanese maple and burning bush. Some years, both clusters bloom; other years, one or both are buried in snow. I often wonder what it’s like to be a snowdrop living an entirely subterranean existence for most of the year, waiting blindly for a spring that may never come.

What do the snowdrops do when they are blanketed in deep snow? Do they sprout regardless, bruising their leafy heads on an unforgiving ceiling of snow? Or do bulbs wake only when the sun herself warms the earth they sleep in, some slumbers lasting years rather than months while perennial hopes lie buried and waiting?

Next Page »