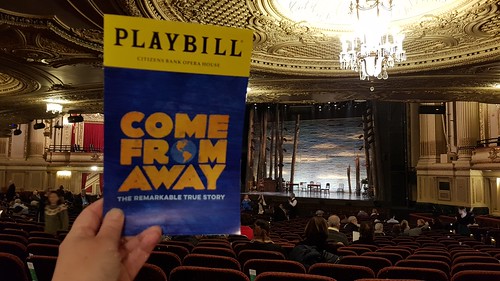

Today J and I drove down Beacon Street into Boston. It was the first time we’d been in the city since March 1, when we saw Bobby McFerrin perform at Symphony Hall: our last normal outing during the Before Time, before we went into quarantine on March 14.

It was strange to drive from Newton into Brookline then Boston after so many months at home. As we passed Boston College, we didn’t see a soul, and at Cleveland Circle, we saw teams playing softball while wearing masks, as if that was how the sport was supposed to be played. As we drove through Kenmore Square and into the Back Bay, we marveled at empty parking spots–plenty of street parking in a town where parking is always at a premium.

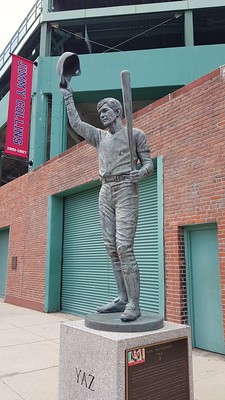

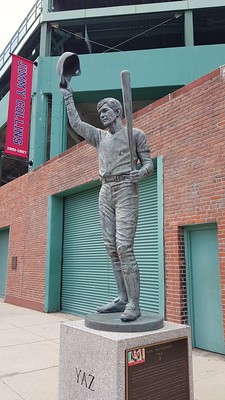

We’d driven into Boston to see the new Black Lives Matter mural outside Fenway Park, so after turning around in the Back Bay, we drove back to Kenmore Square, parked on Beacon Street near Boston University, and walked toward Fenway. In a city of pedestrians, we had the streets and sidewalks largely to ourselves–yes, there were other walkers, but not near the number we’d normally see, and nearly all of them masked.

It was outside Fenway Park where things started to feel weird. We’ve been avoiding places where we might encounter large groups of people, but there were no crowds around Fenway, and in pre-pandemic times, there were always crowds around the Park: throngs of baseball fans on game days, and throngs of sightseers every other day. The relative absence of people was odd, eerie, and preternaturally unsettling.

Lansdowne Street was open to pedestrians, with tables set up for people to eat outside–and there was indeed a handful of people enjoying a sunny summer day while dining al fresco. But there were no vendors hawking baseball programs, no gravel-voiced ticket scalpers, no jugglers or caricature artists or stilt-walkers. There was a lone vendor selling sausages from a cart who asked almost apologetically if we wanted a cold beverage, and after initially demurring, we turned around, said yes, and tipped him $7 for a $3 soda: the least we could do.

That is when we heard the crack of a bat and the roar of canned crowd noise from inside the park as an announcer intoned the next player at the plate. It was game day in an age with no fans in the stands, players competing for a TV audience and a handful of cardboard cutouts while the streets outside were nearly empty.

Walking up Lansdowne Street hearing the sounds of a game played to an empty ballpark, I remembered all the times J and I have gone to games at Fenway Park, cheering ourselves hoarse in the outfield bleachers before streaming down the stairways and flooding into the street with thousands of other fans. The empty streets around Fenway felt simultaneously apocalyptic and surreally normal: on the one hand, so many COVID dead; on the other, the allure of spectator sports and casual outdoor dining.

Google tells me that Fenway Park held 37,731 fans in the Before Times, when living souls packed the stands. Google also tells me that as of today, 162,000 Americans have died of COVID-19. Do the math: that’s more than four Fenways of fans who have been struck, flied, or forced out, game over. What have we as a nation done to mourn these, our presumably beloved dead? Instead of mourning or even pausing, we’ve instead rushed to reopen for the sake of the economy, for the sake of our sanity, for the sake of denial in an amnesiac age.

“Black Lives Matter,” that mural outside Fenway says…but what about the lives of all those lost grandmothers, grandfathers, aunties, uncles, and elders? What have we done to remember and mourn in our rush to return to normal as if none of this–including the lives and deaths of all those lost souls–had ever happened?

During the early days of the pandemic, we often told ourselves that we were all in this together, but now we each navigate these strange days on our own: some of us still sheltering at home, others venturing out and congregating. I remember the first Red Sox game J and I went to after the Boston Marathon bombing: it was both scary and reassuring to be outside in the sun with other fans, game day being a soothing ritual that brought us all together into the reassuring embrace of an anonymous crowd.

These days, though, crowds are places of contagion, and we steer clear of strangers whose faces are shrouded behind bandanas, gaiters, and masks of all kinds, all of us struggling to get back to normal in a time that is anything but. Who haunts the streets around Fenway Park on a sunny August day: are they the ghosts of those we’ve lost, or our memories of game days past?