On Saturday as I approached the Museum of Fine Arts, I saw a young couple walking ahead of me. It’s not unusual to see young couples walking in Boston, but what caught my eye was the young woman’s pink, pointy-eared hat. Although I’d read about the Pussyhat Project and knew knitters across the country have been making pink hats for the Women’s Marches that will take place across the nation next Saturday, I’d never seen a real live pussyhat in the wild.

As I watched the couple ascend the stairs to the Museum’s Fenway entrance, I knew what I had to do. Although my own hat is black and store-bought, I’m planning to attend next week’s Boston Women’s March for America, and I realized it was time to come out as a Pussyhat-in-Hiding. Since my museum membership allows me one guest, I approached the couple as they stood in line for tickets, complimenting the woman on her hat and offering to get her into the Museum for free.

While her boyfriend bought his ticket, “N” and I chatted about next weekend’s march: she is knitting pussyhats to give away to marchers, and I’m looking forward to marching even though I don’t have a pussyhat to wear. You can see, I suspect, where this is going. By the time her boyfriend had bought his ticket, “N” promised to mail me one of her knitted hats, and I gave her my email address to arrange logistics. None of this would have happened, of course, if “N” weren’t wearing a pink knitted hat with cat ears that inspired me to approach her. The simple act of seeing someone in a distinctive (and politically significant) hat inspired me to reach out rather than quietly minding my own business.

There’s nothing stopping any of us from walking up to a stranger and doing something kind: inviting “N” to be my Museum guest cost nothing but the nerve to approach her. And yet, I would have never dreamed of walking up to a stranger before November. Suddenly, the election of a man who promised to Make America Hate Again makes simple acts of kindness feel subversive and powerful, a revolution powered by knitting needles and nice gestures.

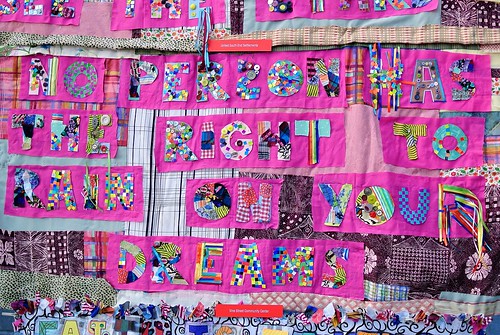

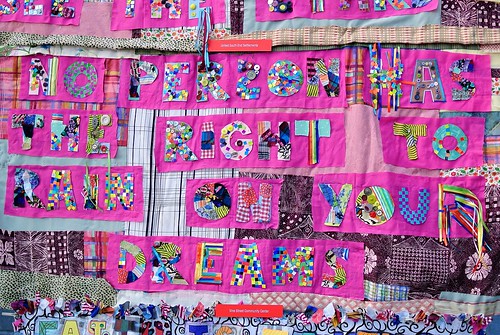

Inside the Museum, in the sun-drenched enclosed courtyard that connects the building’s old and new wings, there are artworks made by local schoolchildren in honor of Martin Luther King Day. The most eye-catching of these are quilts bearing quotations from King, each letter whimsically decorated: a chorus of colors.

These quotes from King seem particularly relevant in today’s political climate, when the voices of hate have grown loud and it’s easy to give up hope. “I have decided to stick with love,” one quilt proclaims. “Hate is too great a burden to bear.” I’ll confess to carrying more anger than I’d like these past few weeks, unable to fathom how some voters could choose a mean-spirited, hot-headed bully over a woman with a lifetime of experience. But this, indeed, is a burden too great to bear: as King himself exhorted, “We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.

So how do we move forward, regardless of the burdens we carry? Dr. King said “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter,” so what are these things? From where I sit, kindness matters, and so does compassion. Truth matters, even if some don’t want to hear it. Lending a helping hand matters, as does protecting the sick and vulnerable. Love matters, and random acts of kindness, and both solidarity and sisterhood. So next Saturday in Boston and beyond, women and men of all colors and stripes will march together for what matters: a chorus of colors, beautiful and harmonious.