August 2017

Monthly Archive

Aug 28, 2017

On my way to a meeting at Framingham State last week, I stopped to take a handful of pictures. Behind one of the academic buildings, a green vine was climbing a brick wall, and below that was a tall, lush stand of Asiatic dayflower abundantly blooming.

Dayflowers are so named because each blossom lasts for only one day: bloom today, gone tomorrow. But you’d never know that by simply looking at any given cluster of dayflowers, as each plant blooms with fervent, verdant abandon. Tomorrow, there will be new dayflowers to replace today’s: one cohort arriving as another retires, a rolling legacy of bloom after bloom.

Admiring a patch of dayflowers is kind of like teaching first-year college students: every year, a new crop of youngsters arrives, the whole world new and full of opportunity. College campuses stay evergreen through a continual influx of new students, and this is one of the things that keeps me from becoming too jaded. What’s old-hat to me is new and exciting to my students.

The strange thing about teaching, however, is the simple fact that I grow old, but my students never do. The freshmen I teach today, more than two decades after I started teaching, are just as young and green as the ones I’ve ever taught. Whenever I grow frustrated with the feeling of having repeated myself over and over and over on some incredibly basic point, I remind myself that this is the first time my students have heard this lesson from me, or possibly at all.

I wonder if dayflowers have any idea how short their flowering lives are, or if they have any idea of anything at all? Is any blooming day a good day if you’re a dayflower, or are some days simply better and more sunny than others?

Today was, I’m guessing, a good day to be a dayflower–sunny and warm, but breezy and comfortable in the shade. If you bloom for only one day, what basis would you have to compare your life with any other? Any day is a good day if you’re young, green, and open to the sun.

Aug 25, 2017

Classes at Framingham State start the Wednesday after Labor Day, so I have just under two weeks of summer left. During that time, I’ll cram in all the semester prep I’d intended to do over the past two months: just like my students, I invariably leave everything until the last minute.

The prelude to back-to-school conveniently coincides with my favorite part of summer: late August, when the sun is starting to lean low toward the horizon. The days are still warm, but the nights have a touch of chill, and both the cicadas and crickets are amping up their summer songs, squeezing as singing as they can into waning days.

In June and July, summer seems as endless as the days are long. In late August, however, you’re reminded that time is slippery and the summer short, and that makes every day that much sweeter.

Aug 22, 2017

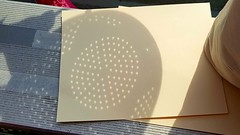

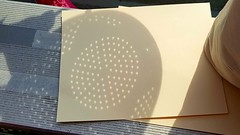

Yesterday was the much-awaited Great American Eclipse, a celestial event that spanned the continent and consequently garnered a great deal of media buzz. Although New England was outside the path of totality, partial solar eclipses are interesting in their own right, so months ago I bought eclipse glasses, looking forward to an opportunity to let my inner science nerd shine.

One of the things that struck me about yesterday’s eclipse was its (literally) universal aspect. The sun shines on rich and poor alike, white and black, left and right. Everyone looks funny and feels foolish wearing eclipse glasses, and everyone’s first remark upon seeing a bite bitten out of the sun is some variation of “Oh, wow!”

Eclipses are wonderful but not surprising: these days, we know far in advance when, where, and to what degree an eclipse will occur. But much of the wonder of any eclipse is the very fact that it happens just as predicted. We say “Oh, wow” because the bite nibbled out of the Vanilla Wafer sun happens just as expected and right on schedule. It’s the wonder of holding a newborn infant and counting her tiny fingers and toes: exactly ten of each, just as it should be.

It comes as news to no one that we are a divided nation, but as soon as we step outside and look up, we find something we all share. Yesterday here in lush and leafy Newton, neighbors spontaneously gathered at the local ballfield, each of us drawn to its wide, unobstructed sky. And just like that, a set of suburban Little League bleachers was transformed into an observation platform peopled by armchair astronomers.

Some of us had eclipse glasses and others had homemade pinhole viewers made out of cereal boxes; everyone shared. One boy showed off a richly illustrated National Park Service booklet about eclipses, and I held aloft a kitchen colander I’d brought, casting a constellation of pinhole crescents onto a piece of cardstock. It was, I’d guess, the kind of ragtag gathering that happened in lots of neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces across the country yesterday: a spontaneous gathering of strangers that fell into place because word had gotten out that something special was happening. All you had to do to join was go outside and look.

And here’s the shocker: the sun is there every day, and so are your neighbors. Yesterday offered a rare and special light show, but every day there are weird and wonderful things happening in place you might not expect, but can readily see if you’re outside and looking.

Yesterday as we were sitting on the bleachers gazing skyward, an enormous bug suddenly zoomed and buzzed us. It was an aptly named cicada killer wasp carrying a cicada that looked twice its size. Nobody could have predicted a two-inch wasp carrying an even bigger bug would fly by at exactly that moment, but we shouldn’t have been surprised. Cicadas, like the sun, are almost ubiquitous in August, and so too are the wasps that sting and paralyze them before dragging them underground to serve as living larvae-food.

It’s a weird and wonderful world out there: sometimes we’re expecting signs and wonders, and sometimes they shock and surprise us, buzzing right by our upturned faces. As the sun gradually grew back into its usual round shape, J and I walked toward home with a neighbor, startling a pair of strolling turkeys before meeting up with another neighbor walking the other way.

He’d viewed the eclipse at home with a pinhole viewer with his kids, he said, but he hadn’t seen it directly. Leaving him with a pair of eclipse glasses, we told him to wait until the clouds cleared and then look up. Although we left him there alone, I can predict what he said the moment the clouds parted: some variation of “Oh, wow!”

Aug 20, 2017

Today J and I drove to Salem, MA to visit the Peabody Essex Museum. Before we went inside, we took a detour around the block to see What the Birds Know, a stickwork installation by Patrick Dougherty.

Dougherty is the same artist who created The Wild Rumpus, a stickwork installation I’d seen at Tower Hill Botanic Garden (and subsequently blogged) last October. Although the two pieces are crafted from the same materials and share a similar whimsical vision, their markedly different surrounding make for two distinctly different impressions.

The Wild Rumpus is located in the woodsy shade alongside a sunny field: the “middle of nowhere” if you’re a child walking with your parents. Inspired by the classic children’s book Where the Wild Things Are, Dougherty’s Tower Hill installation feels wild, or at least woodsy. Looking through its wicker-like windows, you half expect to see deer or other shy forest creatures staring back at you.

What the Birds Know, on the other hand, is at the corner of a busy intersection in downtown Salem. Tucked into a tiny yard next to a historic house, What the Birds Know is surrounded by neighboring buildings and receives lots of visitors. (J and I had driven past it last October, when Salem was thronged with Halloween tourists, and we didn’t even try to photograph it.)

Dougherty’s Salem installation doesn’t feel wild, but cozy: a cluster of neat little houses tucked right alongside human habitations. What the birds of downtown Salem presumably know is how to make a tame and tidy nest right alongside the comings and goings of preoccupied human beings.

Aug 18, 2017

After spending too much time this week glued to my bad-news feed, on Wednesday afternoon I stepped away from my desk to do some errands in West Newton. There, in the deep-slanting light of a summer afternoon, a sprawling tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) stood, its boughs brimming with clusters of yellowish, pink-tinged seeds.

I’ve seen trees of heaven before, but I’ve never been stopped in my tracks by one. The species is invasive and often grows in places where other trees can’t, like urban alleys and streets: the tree that famously grew in Brooklyn was a tree of heaven. But a gangly “ghetto palm” sapling in an alley is quite different from a full-grown tree setting down roots next to a grassy ballfield, with ample room to spread an expansive crown.

When I got home, I looked on Google Maps to see if the playground in West Newton has a name, and indeed it does: Eden Playground, a fitting place for a tree of heaven to grow. Female trees of heaven bear samaras, which are winged seeds that spin like helicopters as they fall, and right now the tree at Eden Playground is heavy-laden with them. Whereas maple samaras have twin seeds with wings shaped like rabbit ears, trees of heaven bear clusters of single-seeded samaras, each one twisted like a egg noodle.

Before setting out to do errands on Wednesday, I started reading Strong for a Moment Like This, a collection of daily prayers and Scripture meditations the Reverend Dr. Bill Shillady emailed to Hillary Clinton during last year’s presidential campaign. (A more sensational title for the book would have been “Hillary’s Emails.”) I became curious about Rev. Shillady’s book after reading his oft-shared (and, unfortunately, partially plagiarized) email to Hillary the morning after her defeat to Donald Trump. I suspect I’ll need lots of prayer and devotion to get through the next four years, or however long it takes our country to jump off the Trump Train.

Trees of heaven are quick-growing but not long-lived: who knows how long the one in West Newton (or her forebears, since this tree spreads via suckers as well as seeds) has been quietly growing in an edge of forgotten soil behind a gas station. What ballgames has she witnessed, and what playground dramas? How much car exhaust and human angst has she absorbed, exhaling oxygen to the clouds? With her toes in the earth and her arms spread toward the sky, this tree of heaven enjoys the best of both worlds, rooted in the dirt but stretching toward the heavens.

These days I genuinely wonder how we can collectively spread our limbs toward love, the only counter to hate. I struggle with this personally, as my grudge-holding heart sometimes feels as twisted as a spinning samara. Is more prayer necessary, or more devotion? If I were Hillary Clinton, I’d still be doubled-over with rage, as I was the morning after the election and still sometimes am when I scroll my bad-news feed. How can we sprout from the dirt of division and expand into the flower and fruit of love?

There is, I trust, no hate in heaven, not even righteous indignation; I believe hate gets stripped away in the wash of God’s love. But here on earth, where meanness rages, lies are perpetuated, and the evil and greedy reap great rewards, where does the God of justice hide?

Into this life a little light falls, as do spinning samaras, and occasionally trees have ample room to spread and shine. Perhaps that is the only taste of heaven we’re presently permitted.

Aug 14, 2017

After spending Saturday with a friend in central Massachusetts, I stopped on my way home at Saint Joseph’s Abbey, a Trappist monastery in Spencer.

Decades ago, I’d visited Saint Joseph’s as an exhausted graduate student at Boston College. The campus ministry program there had advertised a silent weekend retreat at Mary House, a retreat center right next door to the Abbey, and I jumped at the opportunity to take a weekend away from my life as a frazzled grad student juggling teaching with my own studies.

Several campus ministers ferried me and a group of undergraduates–I was relieved that none of them were my own students–to the Mary House, where they provided an abundant supply of food and gave us the freedom to spend the weekend however we wanted. We came together for meals, which we ate in silence while one person read to the rest of us, a monastic practice known as “refectory reading.” Apart from meals, we were free to come and go as we pleased, either staying close to the Mary House or venturing over to the monastery grounds.

I don’t remember much from that decades-ago visit to Saint Joseph’s Abbey, but I do remember how lovely the grounds were. I spent one day walking the grounds with its rolling hills, beaver ponds, and wild turkeys, and the beauty of the landscape seemed to reflect the tranquility of the monks’ practice.

I also spent a lot of time on that retreat tucked away in visitors’ chapel, which was (and is) tiny, dark, and cavernously quiet, like the bottom of a deep well. If you visited the chapel during one of the regularly-scheduled prayer times, you could hear but not see the monks reciting the Office from their choir stalls, which were contiguous to but visually hidden from the chapel pews: no peeking.

Since I hadn’t come to Saint Joseph’s to peer at monks, I’d intentionally visit the chapel during off times, when I knew no one else would be there. To me, the draw of the place wasn’t the presence of mysterious monks: I’d read enough Thomas Merton to imagine what the life of a monastic was like. Instead, I went to the chapel to drink in the silence left behind after the monks had gone. As an inactive Catholic who had practiced Zen meditation for years, I craved the deep steep of silence the Abbey church provided, its stone walls almost oozing with prayer.

Yesterday as I drove the winding road to the Abbey church, its stones unchanged over the several decades since I had last been there, my heart was heavy with the news of the world: white supremacists marching in Charlottesville, the Denier in Chief sowing discord from the White House, and the threat of nuclear annihilation looming everywhere. How can you retreat to a silo of silence when the the world is on fire? Or, better yet, how can you not seek spiritual solace then?

The visitors’ chapel was just as tiny and dark as I’d remembered, and the silence was just as profound. After briefly praying in the shadow of an altar illuminated by a stained glass image of Mary and the infant Jesus, I went back outside to admire the monastery fields bathed in the long-angled light of late afternoon.

And that is when I saw him: a lone, white-robed monk walking down a quiet road through a grass-green field. In the distance, a flock of geese moved through the grass, either grazing or floating in an invisible pond hidden behind the crest of those rolling hills. The monk walked slowly, deliberately, neither hurrying nor dawdling, and he stopped briefly to look at the same geese I was watching. Surely the scene was just as idyllic and lovely from his perspective as it was from mine.

The world is on fire, and everywhere people are consumed in the flames of anger, fear, and bigotry. Where can you find the still, small voice who wants nothing more than to help this suffering world?

Aug 10, 2017

Earlier this week, I watched a viral video of Jimmy Fallon meditating on The Tonight Show with Andy Puddicombe, co-creator of the Headspace meditation app. While Puddicombe walked Fallon through a guided meditation on The Tonight Show couch, the show’s band and studio audience participated in their seats, the camera showing them sitting quietly with closed or downcast eyes, following their breath.

Meditation isn’t new to me; it’s something I’ve been doing daily for years. But it was remarkable to see an entire studio audience of ordinary people meditating in the most ordinary way–in their seats, in the midst of watching a TV show, without any suggestion that meditation should be hidden away in a mystical, mysterious place, far removed from daily life.

These days I meditate at my desk because I’m much more likely to do it if I do it where I’m at. There’s no room for excuses: there’s no putting off getting up out of my chair and heading to my cushion, and there’s nothing to pull out or dust off. Dragging myself onto a meditation cushion takes a bit of effort, but there’s nothing more natural than me sitting at my desk, my back upright and my feet flat on the floor, while I watch my breath for ten minutes or so before picking up my pen to write.

Some would argue it’s too difficult to meditate at one’s desk, in the very midst of one’s daily distractions, and I suppose that’s true for many people. But if I can’t meditate at my desk, in the very heart of my life, what business do I have saying I can meditate anywhere else?

The Jimmy Fallon clip wonderfully illustrates something teachers in my Zen school often say: meditation is nothing special. It’s not some otherworldly activity that grants magical powers; instead, it plugs you solidly into the life you already live. If you breathe and have a body and a mind, you have the three things–the only three things–necessary to meditate.

There’s nothing wrong, of course, with meditating in a special place surrounded by special things: the whole purpose of the “smells and bells” of formal Buddhist practice–the robes and cushions and altars and incense–is to put your mind into the mood for practice, just as candlelight and fine china turn an ordinary dinner into a romantic meal. But just as a fancy candlelit dinner isn’t necessary for romance–lovers will love regardless of where or what they’re eating–you can meditate anywhere and anytime, with or without special accoutrements. When it comes to meditation, the main requirement is to come as you are.

Aug 8, 2017

One of the central concepts in Buddhist philosophy is that of impermanence. The Buddha said people suffer because they cling to things, beings, and experiences that pass away. Life is great as long as you have and hold the things you love, but nothing gold can stay. Children grow up and move away, our bodies age and grow old, and even our newest and shiniest belongings wear out and lose their sheen.

Impermanence isn’t a tenet you have to believe; like gravity, it’s a natural law you’ll notice if you open your eyes. This past weekend, J and I saw the ruins from a massive fire that recently destroyed a luxury apartment complex in nearby Waltham. (Fortunately, since the complex was still under construction, nobody was living there.) It was stunning to see a hulking pile of rubble where there had recently been five multistory buildings.

J and I weren’t the only ones looking at the fire’s aftermath: every car we saw pulling into a nearby municipal parking lot slowed down to take a look as it passed. We all know, intellectually, that we can lose everything we own in an instant, but this lesson doesn’t hit home until you see the charred wreckage of someone else’s dream.

Aug 5, 2017

Ever since I decided to go to my 30-year high school reunion last month, I’ve been sorting through old photos and mementos from my school days, photographing and posting them online as a way of making a digital backup of the analog artifacts of my early life. Yesterday, I photographed and posted two photos from kindergarten: first, my class portrait, and second, a composite photo of everyone in my kindergarten class from Barnett Elementary School in Columbus, Ohio.

I’m Facebook friends with two members of my kindergarten class, and I recognize and remember a handful of other classmates I’ve since lost touch with. But the names and personalities of the other children in that composite photo are lost to time. I remember my kindergarten teacher, Miss Mock, and I remember vague details about our classroom, like the fact it opened onto its own brick-walled playground and had in one corner a playhouse with toy kitchen utensils and costumes for playing dress-up. But everything else is a blur.

I remember learning in kindergarten not to be a tattletale, even though I was greatly aggrieved that Miss Mock didn’t spring into action when I dutifully “tattled” that some now-forgotten boy was doing something both dangerous and forbidden in that walled-in playground. Wasn’t preventing a child from braining himself on the concrete a more pressing priority than teaching me, an obedient and good child, an abstract lesson about minding my own business?

Clearly I was wrong: Miss Mock wasn’t concerned that so-and-so would fall from whatever it was he wasn’t supposed to be climbing, and indeed nobody was hurt that day. But the lesson–or, more accurately, my sense of outrage that I was being scolded for following the rules while a boy who was doing something naughty got no scolding whatsoever–clearly stays with me. In retrospect, this might have been the most valuable lesson I learned in kindergarten: not a lesson about tattling, but a lesson about life’s unfairness. Sometimes good girls get scolded and bad boys get away with being naughty, a lesson I suspect many women would understand.

The only other experience I remember from kindergarten involves wooden blocks. One day I was playing with blocks, and a little boy knocked over the tower I was patiently building. (As a child who grew up with older sisters, I hadn’t realized until kindergarten how senselessly cruel little boys could be.) Enraged, I picked up a block and promptly threw it directly at the little boy’s head. It was a clear instance of vigilante justice: you touch my toys, I bean your brain.

Except…after hitting the boy, I immediately started crying, upset at the bad thing I’d done. (Have I already mentioned I was an obedient and good child?) I don’t remember if the boy cried because I’d hurt him; I was probably too upset to notice. Instead, I was completely overwrought by the tiny tragedy that had played out: first he ruined my tower, then I hurt him in return.

When Miss Mock asked what happened–as I remember, this all transpired in a split second when she was out of the room, so a more savvy child would have denied everything or pinned the blame on someone else–I gushed out a tearful confession: “He did this, I did that!” Ultimately, I think I was more wounded from the encounter than he was. The boy whose name I no longer remember presumably rubbed off the bump to his head, but I was heartbroken to think I’d hurt someone simply because they made me mad.

Aug 2, 2017

I’m currently reading Michael Finkel’s The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit. The book tells the story of Christopher Knight, who lived alone in the Maine woods for 27 years before being arrested for burglary in 2013. The book reminds me of Into the Wild, the book Jon Krakauer wrote about Christopher McCandless, except that while McCandless died after 100 solitary days foraging in the Alaskan wilderness, Knight survived for more than a quarter century on food and supplies he stole from nearby cabins.

With both books, the question of “why” spurs readers onward. In Krakauer’s book, you eventually learn that McCandless didn’t intend to live his entire life as a hermit: during part of his journey, he befriended others, and he intended to return to civilization after his Alaskan sojourn. McCandless was a social, likable fellow when he was around people, and after living on his own in Alaska for several months, he intended (and tried) to leave the wild. It was a cruel accident, in other words, that McCandless died a hermit’s death.

Knight, on the other hand, is a true solitary, but it isn’t immediately clear why he shuns human contact. Knight returns to civilization unwillingly. After burglarizing area cabins for more than two decades, he is captured and thrown in jail: a hermit tossed in with criminals. McCandless had specific reasons for shunning his family, but Knight doesn’t seem to hold any animus toward his family in particular or society in general: he just chooses a solitary path.

McCandless died at the age of 24, but had he lived, he would now be 49 years old: a middle-aged man approaching fifty. Knight survived his stint in the Maine woods, and he was apprehended and arrested at the age of 47. The hermetic lifestyle holds a certain appeal when you’re young, but how does it hold up as you approach middle age?

We can write-off Chris McCandless’ quest as the wayward ways of a young man who hadn’t yet found himself: Krakauer, who wrote McCandless’ story when he was 42, looks back upon his own youth and finds parallels between his life and that of his subject. But if youthful restlessness similarly drove Knight to the forest, what is it that kept him there?

We’ve all probably had times when we’ve wanted to abandon our obligations and escape into the wild, but those of us who are middle-aged presumably outgrew those inklings, choosing instead to settle down and get serious about the business of homemaking, starting a family, or pursuing a career. But Knight sidesteps all those presumably normal pursuits, walking into the woods at the age of 20 and showing no signs of wanting to return. How do you live 27 years of your life in a solitary camp with nothing but a long list of burglaries to your name? Wouldn’t you at some point decide to pursue another path?

This is what keeps me reading: I want to see what would keep a man in the woods for over two decades. I can understand the impulse that would drive a person to leave society, but not necessarily the fortitude that would keep him away.

Today’s photos come from a solo trip to Maine I took in September, 2004 and blogged here.